How AI Voice Cloning Works A Student’s Guide

Introduction

You’ve heard a podcast host say “we’ll be right back” but what if that familiar voice wasn’t recorded live, or even spoken by the person at all? Welcome to the world of AI voice cloning: a field that can replicate a person’s voice so convincingly that it’s increasingly hard to tell synthetic from real. For students studying machine learning, media literacy, or digital ethics, understanding how voice cloning works is now as important as learning data structures or source citation.

This article walks you through the technical building blocks (what neural networks and speaker embeddings do), the pipeline from raw audio to a cloneable voice, why the technology is suddenly so good (and fast), and the practical and ethical questions it raises. I’ll reference the most influential research, summarize what leading companies offer, explain how detection and regulation are evolving, and give actionable tips you can use in projects or classroom discussions. Expect clear examples, short case studies, and concrete resources so you can both experiment safely and think critically about real-world impacts.

1. The basic pipeline from recording to cloned speech

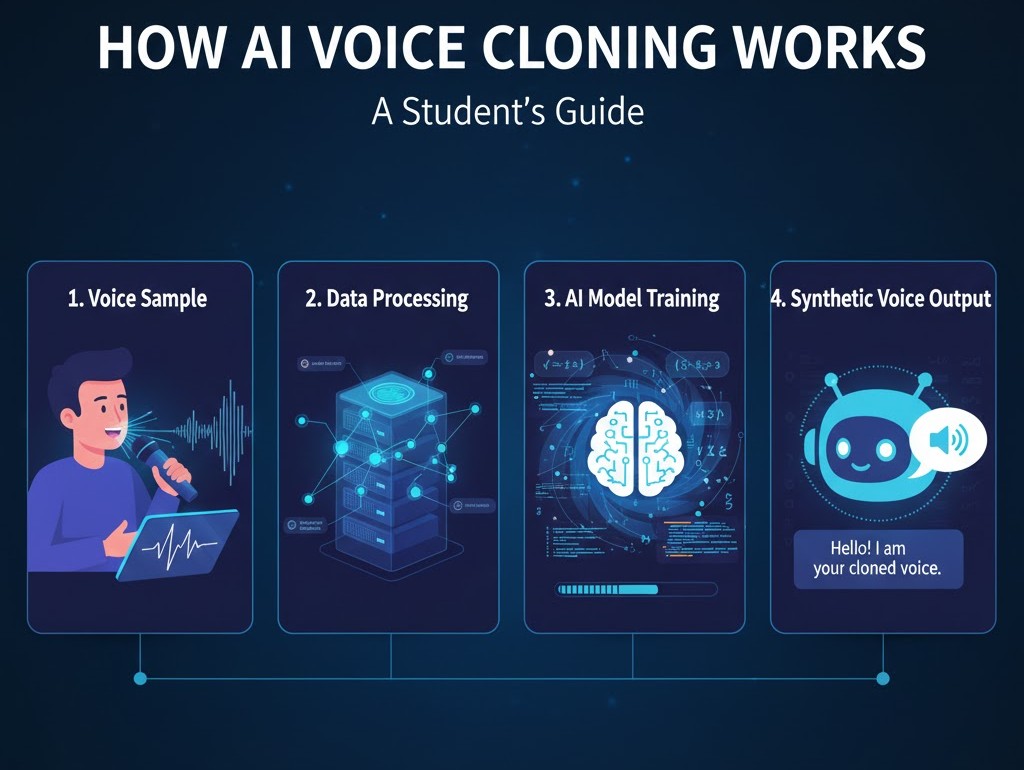

At its core, modern voice cloning is a pipeline with three main stages:

-

Speaker representation (encoding). A short audio sample (seconds to a few minutes) is transformed into a speaker embedding a fixed-length vector that captures timbre, pitch habits, cadence, and other identity cues. Techniques include d-vectors and x-vectors.

-

Text-to-spectrogram model (synthesis). A model like Tacotron 2 converts text (or phonemes) into a mel-spectrogram a time-frequency map that describes how the voice should sound over time. This model is often trained to condition on that speaker embedding so output matches a specific voice.

-

Neural vocoder (waveform generation). The spectrogram is turned into an audio waveform by a neural vocoder such as WaveNet, WaveRNN, WaveGlow, or HiFi-GAN. This stage determines the naturalness and audio quality.

Why this split matters: separating identity (embedding) from linguistic content lets a system generate any sentence in the target voice after seeing only a short sample, and it also enables cross-speaker transfer (e.g., use one model for many voices).

2. Speaker embeddings the identity fingerprint

Modern systems don’t “store” voices like audio files. Instead, they compute a compressed fingerprint (embedding) that summarizes what makes a voice recognizable.

-

D-vectors (derived from GE2E training) and x-vectors (from speaker-recognition models) are two common approaches. These embeddings are compact (hundreds of dimensions) and trained so utterances from the same person are close in vector space.

-

Embedding models are trained on thousands of speakers (VoxCeleb and similar datasets), which helps them generalize to new voices with limited samples. The better the embedding, the more convincing the cloned voice will be.

Classroom tip: try extracting embeddings from short clips (many open-source tools exist) and visualize them with t-SNE to see how speakers cluster.

3. Synthesis models: Tacotron, Transformers, and their descendants

Tacotron 2 (Google) set the standard by mapping text directly to mel spectrograms with a sequence-to-sequence network and attention. The result: natural prosody and intonation that closely mimic human speech patterns. Many modern systems extend this idea with transformer architectures or multi-speaker conditioning to improve speed and robustness.

Why prosody matters: prosody (rhythm, stress, intonation) is what makes synthetic speech feel alive rather than robotic. Synthesis models that handle prosody well reduce the uncanny valley and improve perceived authenticity.

4. Neural vocoders: the final polish

Neural vocoders convert spectrograms into waveforms. WaveNet was the breakthrough for quality, but it’s computationally heavy. Lighter alternatives (WaveRNN, WaveGlow, HiFi-GAN) strike different tradeoffs between compute cost and audio fidelity. Benchmarks show WaveNet still ranks high in MOS (listening quality), though newer models deliver very good quality at lower latency.

Practical note: for real-time cloning (e.g., voice actors or agents), developers pick faster vocoders even if they sacrifice a small amount of naturalness.

5. How little data is needed? One-shot and few-shot cloning

Recent research and tools can generate convincing voice clones from mere seconds of clean audio, though quality and speaker similarity typically improve with more data. One-shot methods use powerful speaker encoders that generalize from very little speech; few-shot approaches (30s–2min) remain the sweet spot for near-professional clones. Surveys of recent literature (2024–2025) confirm that embedding quality, dataset diversity, and vocoder choice all affect how much sample time you need.

6. Real-world examples & companies

Several companies offer voice cloning as a service, with diverse use cases:

-

ElevenLabs and Respeecher provide high-quality cloning for podcasts, audiobooks, and media localization. These services often include consent workflows and commercial licenses

-

Research projects and open-source toolkits (NVIDIA Tacotron2, Real-Time-Voice-Cloning repos) let students prototype and learn the tech.

Case study (media): studios sometimes use cloned voices for ADR (automated dialogue replacement) and dubbing, saving time and preserving actor timbres when schedules clash[, but they usually require signed consent.

7. Risks, misuses, and societal impact

Voice cloning’s dark side is real and accelerating. Law enforcement, security researchers, and journalists report an uptick in AI-enabled scams including “virtual kidnappings” where criminals clone a loved one’s voice to extract money. The FBI and media outlets have warned that these attacks are becoming more frequent and convincing.

Key harms include:

-

Fraud and impersonation. Voice clones used to authorize transactions or manipulate victims emotionally.

-

Misinformation and reputation damage. Fabricated statements attributed to public figures.

-

Forensic challenges. Synthetic audio can degrade speaker-recognition accuracy used in legal contexts. Recent forensic studies show traditional features (like MFCCs) sometimes fail to generalize across cloning algorithms.

Student reflection: ask how consent, transparency, and digital literacy can be taught together to mitigate these harms.

8. Detection and defenses

Detecting cloned voices is an ongoing arms race. Approaches include:

-

Signal-level features (e.g., spectral artifacts, phase inconsistencies, MFCC anomalies). These work well in controlled settings but struggle with varied real-world recordings.

-

Model-based detectors trained on real vs. synthetic audio. Effectiveness depends on training data coverage; new cloning methods can evade older detectors.

-

Provenance and watermarking. Companies and researchers are exploring inaudible watermarks or metadata attestation that indicate synthetic origin; legal proposals and platform policies also push labeling for synthetic media.

Actionable tip (for projects): if you generate synthetic voices, embed explicit labels in the project metadata, and consider using audio watermarking tools so others can verify origin.

9. Legal & policy landscape (short summary)

Regulation is nascent and fragmented. Some countries are exploring legal protections for one’s biometric traits (voice/image) and fast-take-down rules for non-consensual deepfakes; other mechanisms include industry self-regulation and platform policies requiring labeling. Keep an eye on legislative developments and institutional policies — they change fast.

10. Ethics and best practices for students and creators

If you want to experiment responsibly:

-

Always get informed consent from any speaker whose voice you’ll clone. Put agreements in writing.

-

Label synthetic audio. Make obvious, human-readable statements in descriptions and metadata (e.g., “This audio contains AI-generated voice”).

-

Use synthetic voices for constructive purposes accessibility, creative projects with permission, education, or research that advances detection/ethics.

-

Document your dataset and process when publishing research to help reproducibility and accountability.

FAQs (People Also Ask)

Q: Can voice cloning fool speaker verification systems?

A: Yes advanced cloning can lower the accuracy of automated speaker verification and even fool humans in many cases. Forensics research shows current verification tools can be degraded by synthetic audio, though detection methods continue to improve.

Q: How long of a recording do you need to clone a voice?

A: Quality varies, but many practical systems can create a passable clone from 30 seconds to 2 minutes. One-shot systems exist that attempt cloning from only a few seconds, though they usually sacrifice some speaker similarity.

Q: Is voice cloning illegal?

A: Not inherently legality depends on consent, use case, and jurisdiction. Using a cloned voice to defraud or defame is illegal; some countries are moving toward explicit protections over biometric likeness.

Q: How do major platforms handle synthetic speech?

A: Platform policies are evolving. Many require labeling for synthetic content in ads and political contexts; media firms and TTS vendors often provide consent workflows and licensing controls.

Tags :

No Tags

0 Comments